Aether, Elastic Solid Theory by R. Close and S. Rashkovskiy

Books on quantum mechanics often point out that the theory explains phenomena that had not previously been explained by classical physics [1]. This is true. But one should ask why classical physics failed to explain these phenomena. Was it because classical models are intrinsically ill‐suited to describing nature? Or was it because realistic classical models were too complicated for physicists to analyze?

The historical evidence points to the latter explanation. The earliest conception of the aether consistent with the behavior of light waves was Thomas Young’s observation that light seemed to behave like transverse waves in an elastic solid. This theory was successfully applied to the study of light by a host of now‐famous 19th century scientists, with contributions from Boussinesq, Cauchy, Fresnel, Green, MacCullagh, Navier, Stokes, Rayleigh, Riemann, Thompson (Lord Kelvin), and others (Maxwell used a more complicated aether model to derive the equations of electromagnetism). Yet in spite of the elastic solid’s conceptual simplicity, and the extensive effort spent analyzing it, no exact description of its physical behavior could be produced. The reason for this failure is the non‐Abelian nature of finite rotations. Nineteenth‐century scientists did not have the mathematical tools needed to describe arbitrary variations of orientation, and even modern condensed matter theorists have shied away from the attempt (Kleinert 1989). Today, the mathematics of rotations is well‐understood for quantum mechanical systems. This fact makes it reasonable to suppose that rotations in classical elastic solids might also be described by similar mathematics..

Are there photons in fact? There are two opposing points of view on the nature of light: the first one manifests the wave-particle duality as a fundamental property of the nature; the second one claims that photons do not exist and the light is a continuous classical wave, while the so-called “quantum” properties of this field appear only as a result of its interaction with matter. In this paper we show that many quantum phenomena which are traditionally described by quantum electrodynamics can be described if light is considered within the limits of classical electrodynamics without quantization of radiation. These phenomena include the double-slit experiment, the photoelectric effect, the Compton effect, the Hanbury Brown and Twiss effect, the so-called multiphoton ionisation of atoms, etc. We show that this point of view allows also explaining the “wave-particle duality” of light in Wiener experiments with standing waves. We show that the Born rule for light can easily be derived from Fermi’s golden rule as an approximation for low-intense light or for short exposure time. We show that the Heisenberg uncertainty principle for “photons” has a simple classical sense and cannot be considered as a fundamental limitation of accuracy of simultaneous measurements of position and momentum or time and energy. We conclude that the concept of a “photon” is superfluous in explanation of light-matter interactions [2]..

Quantum mechanics without quanta.. In this paper, I argue that light is a continuous classical electromagnetic wave, while the observed so-called quantum nature of the interaction of light with matter is connected to the discrete (atomic) structure of matter and to the specific nature of the light-atom interaction. From this point of view, the Born rule for light is derived, and the double-slit experiment is analysed in detail. I show that the double-slit experiment can be explained without using the concept of a “photon”, solely on the basis of classical electrodynamics. I show that within this framework, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle for a “photon” has a simple physical meaning not related to the fundamental limitations in accuracy of the simultaneous measurement of position and momentum or time and energy. I argue also that we can avoid the paradoxes connected with the wave-particle duality of the electron if we consider some classical wave field - “an electron wave” - instead of electrons as the particles and consider the wave equations (Dirac, Klein-Gordon, Pauli and Schrödinger) as the field equations similar to Maxwell equations for the electromagnetic field. It is shown that such an electron field must have an electric charge, an intrinsic angular momentum and an intrinsic magnetic moment continuously distributed in the space. It is shown that from this perspective, the double-slit experiment for “electrons”, the Born rule, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle and the Compton effect all have a simple explanation within classical field theory. The proposed perspective allows consideration of quantum mechanics not as a theory of particles but as a classical field theory similar to Maxwell electrodynamics..

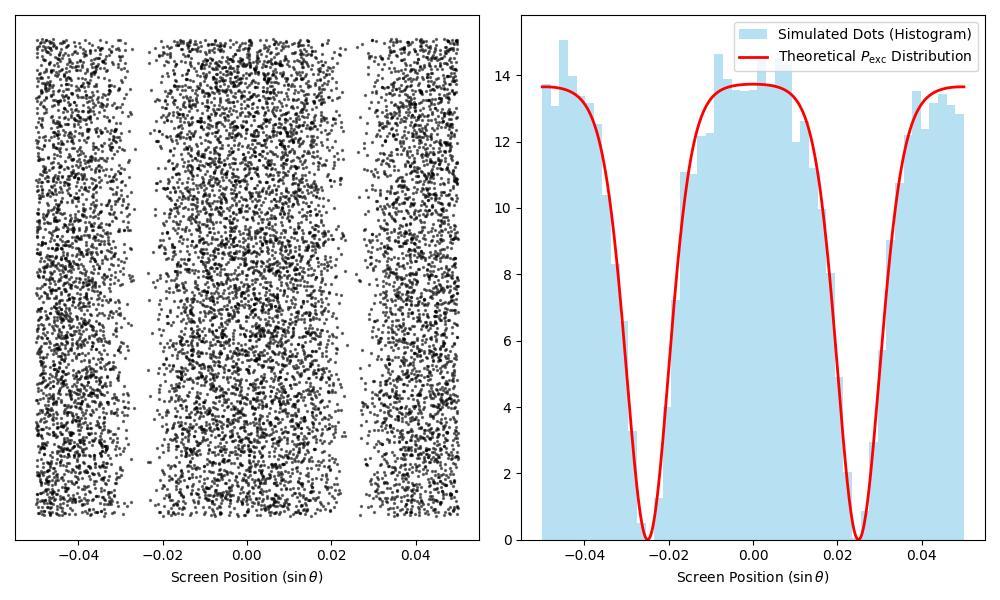

Here [3], I show that the double-slit experiment can be easily explained in terms of classical electrodynamics if we take into account the discrete structure of matter (a screen, a detector) and the specific nature of the interaction of light with matter, which is described by the Schrodinger equation (or other wave equation of quantum mechanics)... The calculation proceeds using the Monte Carlo method: at each time, the probability of excitation of each unexcited (non-ionised) atom will be calculated. The calculation for each atom is continued until its excitation (ionisation) occurs.. Comparing Fig. 1 with the real picture of the “accumulation of photons” on the photographic plate in the double-slit experiment, we see that the calculated pattern is completely consistent with the experimental interference pattern and the model completely reproduces the results of these experiments..

The code below replicates Figure 1 from [3].

D_OVER_LAMBDA = 20;A_OVER_LAMBDA = 4

NUM_ATOMS = 15000; TAU = 5.0

MIN_SIN_THETA = -0.05; MAX_SIN_THETA = 0.05

def relint(sin_theta, d_over_lambda, a_over_lambda):

alpha = np.pi * d_over_lambda * sin_theta

beta = np.pi * a_over_lambda * sin_theta

sinc_beta = np.where(beta != 0, np.sin(beta) / beta, 1.0)

rel_I = (sinc_beta**2) * (np.cos(alpha)**2)

return rel_I

def exctprop(rel_I, tau):

return 1.0 - np.exp(-rel_I * tau)

atpos = np.random.uniform(MIN_SIN_THETA, MAX_SIN_THETA, NUM_ATOMS)

I_over_Imax_at_atoms = relint(atpos, D_OVER_LAMBDA, A_OVER_LAMBDA)

P_exc_at_atoms = exctprop(I_over_Imax_at_atoms, TAU)

random_draws = np.random.rand(NUM_ATOMS)

excited_atoms_indices = P_exc_at_atoms >= random_draws

excited_positions = atpos[excited_atoms_indices]

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.subplot(1, 2, 1)

y_tmp = np.random.uniform(-1, 1, len(excited_positions))

plt.scatter(excited_positions, y_tmp, s=2, color='black', alpha=0.5)

plt.yticks([])

plt.xlabel(r'Screen Position ($\sin\theta$)')

plt.subplot(1, 2, 2)

hist_bins = np.linspace(MIN_SIN_THETA, MAX_SIN_THETA, 50)

counts, edges, _ = plt.hist(excited_positions, bins=hist_bins, density=True,

color='skyblue', alpha=0.6, label='Simulated Dots (Histogram)')

sin_theta_line = np.linspace(MIN_SIN_THETA, MAX_SIN_THETA, 500)

I_over_Imax_line = relint(sin_theta_line, D_OVER_LAMBDA, A_OVER_LAMBDA)

P_exc_line = exctprop(I_over_Imax_line, TAU)

P_exc_line_normalized = P_exc_line / np.trapezoid(P_exc_line, sin_theta_line)

plt.plot(sin_theta_line, P_exc_line_normalized, color='red', linewidth=2,

label=r'Theoretical $P_{\text{exc}}$ Distribution')

plt.xlabel(r'Screen Position ($\sin\theta$)')

plt.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

Chantal Roth: Using simulations and classical field theory (inspired by Maxwell, Kelvin, and recent work by Close and Rashkovskiy), I show how familiar 'quantum' outcomes like spin-½ and Stern-Gerlach splitting can arise from deterministic wave evolution. I also explore the idea that gravity is a form of refraction and that space contraction and time dilation are natural wave effects.

This ontological approach offers intuitive explanations, and may help bridge the gap between quantum theory and general relativity..

In this model, both the Schrödinger equation and also the Dirac equation have a real physical meaning, that is quantum physics has an underlying reality and a wave function is not just a probability density, but consists of actual deformations in an elastic solid – our universe. This elastic solid can be thought of as the 'fabric of space [5]

#Roth #Video #WaveParticle #Aether

Experiments

This document collected some proposed experiments to test the validity of the claims presented here.

References

[1] https://classicalmatter.org/Physics/WhyAether.pdf

[3] Quantum Mechanics Without Quanta

[4] https://arxiv.org/abs/1507.02113

[5] https://elastic-universe.org